Once upon a time, in the ancient city of Constantinople, a girl was born to a bear trainer and an actress. The girl worked in a brothel, and as an actress, before travelling through North Africa and eventually settling back in Constantinople as a wool spinner. Here her beauty, wit and amusing character are said to have drawn the attentions of Emperor Justinian who met and fell in love with the girl, and changed the law to enable them to marry. The girl became Theodora, Empress of the Byzantine Empire, presiding over the birth of Constantinople as the most magnificent city in the world. As legend has it Theodora became a powerful political leader and feminist reformer, expanding the rights of women to own property, introducing the death penalty for rape, providing mothers increased rights over their children, and outlawing the killing of a wife who committed adultery. In 548AD Theodora died of breast cancer, at the age of 48, having been the first woman in documented history to be offered a mastectomy…

Ancient History

Cancer has been with us for thousands of years. The earliest descriptions of breast tumours are found in the Edwin Smith papyrus from Ancient Egypt, but it was Hippocrates – the Father of modern medicine – who named it karkinos, the crab, because of a tumour’s physical resemblance to a crab with outstretched feet, though perhaps he also sensed the surprising rapidity with which the murderous little creature can move, and the pincer-like grip it can exert. Translated by the Romans into Latin, karkinos became cancer, and the rest, as they say, is history. A long and morbidly fascinating history that charts the development of modern medicine, and has brought us to the treatments we take for granted today.

From the Ancient Greeks to the Stuarts, for 1700 years it was believed that breast cancer was caused by an imbalance in the humors – the fluids that controlled the body – and specifically due to an excess of black bile. It was generally considered untreatable, and remained a relatively rare condition, with most women dying too young to develop it and high rates of early childbirth helping to protect against it. During the course of the 18th century, the humoral theory of cancer was rejected, and breast cancer was postulated to be a result of a whole range of female ‘faults’ including too little sex, too energetic sex, childlessness, wearing restrictive corsets, and sitting around on your bottom not doing enough activity. To paraphrase the great F Scott Fitzgerald, show me how a society thinks about breast cancer and I’ll tell you how it thinks about women.

The Century of the Surgeon

Finally, in 1757, Henri Le Dran recognised that surgical removal of the breast could successfully treat breast cancer, providing the infected lymph nodes in the armpits were removed (these being the mechanism by which cancer cells could pass into the body’s circulatory system and spread elsewhere). However, surgery remained primitive and traumatic, with no pain control (beyond a bottle of whisky and a stick between your teeth) and no means with which to prevent wound infection. It was the glorious Victorian age that saw the discovery of antiseptic and anaesthetic, which transformed medical possibilities and ushered in ‘the century of the surgeon’. The magnificent men and their medical breakthroughs are too numerous to mention here, but three examples will suffice to remind us how progress bounced across borders and echoed down the decades. In Vienna, 1847, Dr Phillip Semmelweiss drastically reduced mortality of new mothers by asking surgeons to wash their hands in chlorinated lime. He had pioneered antiseptic. In London, 1853, Dr John Snow gave chloroform to Queen Victoria during the birth of her 8th child. He had popularised anaesthetic. And in New York City, 1852, William Stewart Halsted was born. He would go on to change the destiny of millions of breast cancer patients for generations.

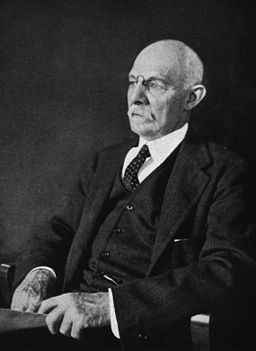

William Halsted was a giant of modern medicine. One of the four founding fathers of John Hopkins Hospital, his credits include pioneering the system of surgical residency training, transforming wound healing through ‘Halsted’s principles’, and introducing the latex surgical glove. And in 1882, he introduced the Radical Mastectomy. Named ‘radical’ for a reason, Halsted’s Mastectomy was based on the theory that aggressive removal of the regional tissue surrounding a tumour would prevent its future spread, and so it required total removal of the breast, lymph nodes and the underlying pectoral muscle. It became the gold standard for breast cancer treatment, with millions of women undergoing this brutal and disfiguring, but ultimately lifesaving, operation.

After all, disability, ever so great, is a matter of very little importance as compared with the life of the patient – W. Halsted, 1894

Across the pond British surgeon George Beatson had developed a hunch that breast cancer wasn’t only about the breast. In 1895 he discovered that removing the ovaries in 3 patients with advanced breast cancer shrank their tumours and improved survival. He had inadvertently discovered the link between breast cancer and hormones produced in the ovaries, and pioneered the oophorectomy as another ‘ectomy’ to treat breast cancer.

For almost a century the Halsted mastectomy was the first line surgical treatment for breast cancer and, in the absence of medical imaging, diagnosis was made through excision. It’s hard to believe now, but until the early 1980s discovering a lump in your breast and signing the surgical consent form meant you might wake up from surgery to find, not only that the lump was malignant, but that half of your chest and possibly also your ovaries had been removed. Given the prevailing attitudes of the time, the stigma associated with cancer, and the brutality of the treatment, it is not so surprising that, subconsciously or otherwise, many women delayed in approaching their doctors.

Thoroughly Modern Mastectomies

It wasn’t until the 1950s that the assumptions underlying the Radical Mastectomy were challenged, and a minority of surgeons began offering simpler mastectomy procedures, but Halsted’s radical mastectomy was considered the safest, ‘proven’ option until the 1970s, when convergent developments in medicine paved the way for a more conservative approach. As more women presented with smaller, less advanced tumours, surgeons increasingly adopted the modified radical mastectomy – removal of ‘just’ the breast and impacted lymph nodes, which is the standard mastectomy procedure as we understand it today. Meanwhile, in 1976 the first clinical trial was published proving that surgical removal of the tumour itself (lumpectomy) plus radiotherapy was equally as effective as mastectomy. At the same time, the dawn of ultrasound, CT and MRI imaging revolutionised diagnostic techniques, enabling surgeons to select the best approach based on the specific needs of the patient, and heralding the modern era of breast conserving therapy.

Today surgeons work with oncologists to determine the best treatment combination for each patient, seeking to strike that elusive balance between maximising the odds of a full recovery, without subjecting the patient to unnecessary, life-altering intervention. That, plus the amazing developments in reconstructive surgery (more on which later) have changed the game for breast cancer patients. Modified radical mastectomy remains the treatment of choice under certain circumstances – for example, if the tumour is large (more than 5cm), if there is more than one tumour, or if there are extensive pre-cancerous cells throughout the breast. And, for those who are found to be at high risk of breast cancer, there is the option of prophylactic risk-reducing mastectomy to remove healthy breast tissue and reduce the risk of breast cancer developing. At the last count, in 2013, around 18,000 mastectomies were performed in the UK every year, with a third of those women going on to have immediate or delayed reconstruction. By any calculation that is a lot of women, having a lot of mastectomies, and spending at least a period of time, by choice or necessity, temporarily or permanently, sans breast. And yet, it remains a topic that – in my experience at least – remains strangely taboo.

When I first found out I had breast cancer I attended a patient workshop, and we did the inevitable ‘go round the room’ to introduce ourselves. Except, of course, when you’re a cancer patient you don’t share your professional achievements and interest in cooking. Instead you share your sad story, and everyone makes themselves feel better about the fact that their story is sad, but nowhere near as sad as the poor sod sat next to them. But this was my first time – I was a workshop virgin, and uninitiated in the fine art of patient politics. True, I did have breast cancer, so things could not be said to be going marvellously for me at this juncture, but I had a clear diagnosis, a tried and tested plan to fix it, I wasn’t rejecting Western medicine to put all my faith in a herbal tea remedy, and I hadn’t been run over by a bus that morning. Honestly, I was feeling pretty good about myself…until I opened my mouth and mentioned the M-word and – after the audible gasps – the whole room looked back at me with fear, pity and naked HORROR in their eyes. Wow. I know my age and family history will often earn me the last brownie, but I didn’t think the mastectomy would be the thing that broke them! If that’s how people who actually have breast cancer feel about it, how on earth is the rest of the world going to react?!

The thing about ‘ectomies’

The thing about ‘ectomies’ is that they are generally a drastic, scalpel led response to some form of disease, and hence they sound absolutely dreadful – hysterectomy, prostatectomy, appendectomy, colectomy; there are 95 different types of ‘ectomy’ and none of them sounds like something you would voluntarily be keen to have. But when I think about ‘ectomies’ I hear Maureen Lipman’s famous ‘ology’ BT advert – “An OLOGY. He gets an ology and he thinks he’s failed! You get an ology and you’re a scientist!” It’s much the same with ‘ectomies’; if you reach a ripe and fruitful old age without having had to contemplate an ‘ectomy’ then you are indeed a winner at the game of life. If, on the other hand, you reach a ripe and fruitful old age as a result of an ‘ectomy’ then your life has still been charmed, though it probably doesn’t feel that way at the time.

How, then, does it feel to have a mastectomy? Well…it’s complicated. There is, to my mind, something inherently positive about a mastectomy. Its purpose is to remove a collection of lethal cells, and drastically reduce the risk of them returning. In my experience, when part of your body has turned against you there is a limit to the level of affection you feel for it, so my overriding reaction in all cases has been relief that the offending article has been safely and cleanly removed like a deadly canister of plutonium, and donated to medical science, or cremated in the blazing flames of an incinerator. Having said that, a mastectomy is an amputation – let us not, for the sake of sensitivity, shy away from calling a digging implement a spade – and you can’t realistically expect to have any part of your body amputated without consequences…

First, there are the physical consequences of a mastectomy. Beyond the surgery itself, mastectomy is often accompanied with aches, pains and limited mobility in the arm, chest and shoulder caused by scar tissue. Removal of the lymph glands under the armpit results in temporary or permanent nerve damage and a lack of sensation, so you could tickle me under the armpit with a feather duster and I wouldn’t be any the wiser. Meanwhile, the disruption to the lymphatic system results in the long term threat, or reality, of lymphedema – a chronic and debilitating swelling of the arm caused by a build-up of excess fluid. Lymphedema can appear months, or years, after treatment, triggered by an infection or injury, which is why mastectomy veterans are fiercely protective if you brandish a knife, needle or sharp nails anywhere near their arms. And, on top of all that, there is the inconvenient and unavoidable fact that what was once convex is now concave; the hill has become a hollow; the breast – whatever shape, form and pertitude it took – has been replaced by fresh air.

This leads us to the practical consequences of life after a mastectomy, and they are, to coin a technical term, a bloody nuisance. Living with a mastectomy means either wearing a prosthesis – a fake plastic boob which is really up there at the pinnacle of unsexy fates that could befall your bra – or opting for a silhouette which is ‘au naturel’ (i.e. awkwardly asymmetrical or Fenland flat). It means careful coordination of clothing to spare the blushes of yourself and everyone you meet. It means scouring the earth for specialist swimwear that doesn’t make you look like a dog’s actual dinner, and making a decent dent in your life savings for the privilege. It means appearing as though you’re curtseying to royalty every time you bend down to pick anything up, lest you flash the world an eyeful of non-cleavage that it definitely doesn’t want to see. It means developing the skills of a contortionist to get completely dressed and undressed under a towel at the gym, and avoid polluting the perfection of the extremist yoga bunny brigade. (Or, alternatively, letting it all hang out and perfecting a defiant ‘Yeah, it’s a mastectomy scar. Namaste!’ death stare that sends them fleeing to their favourite Instagram pose to meditate away the negative energy). It means the exciting prospect of being searched at airports in case you’re really carrying a WMD in your bra, and it means your prosthesis expanding like a balloon under cabin air pressure, so you arrive at your destination, with your extra suitcase full of mastectomy kit, and your special ‘post-surgery’ granny bra straining at the seams, looking like a freakishly lop-sided Jessica Rabbit, waiting patiently for your fake plastic breast to decompress. Who would have thought that not having a boob could be so ridiculously inconvenient and time consuming?!

A matter of little importance

Not that I’m complaining. To echo Halsted, it is a matter of little importance compared to the alternative; stuffing a sock in your bra and being alive is obviously a lottery win compared to never having the opportunity to stuff a sock in your bra because you are dead. It is a matter of little importance…and yet it is a matter of enormous consequence compared to the other alternative of never having had cancer at all. While I am extremely, perversely grateful that my breasts have been removed, I can never be glad. And while most days I have not felt particularly bothered about it, there are others when I have struggled to feel anything but; when walking through the underwear department in M&S has made me sick to the stomach at everything I have lost, and strutting my stuff at the swimming pool has required me to dig so deep for confidence that it has felt altogether preferable to bury myself deep under the duvet. This is the emotional turmoil that comes served with a mastectomy – a potent cocktail of grief and relief, with a dash of positive pragmatism and a bitter twist of regret. However necessary the procedure, however preferable to the alternative, there is no avoiding the fact that you enter the operating theatre with your body intact, and wake up with part of it permanently removed. This is for keeps, and the myriad physical and practical implications are a nagging, daily reminder of the ordeal you have suffered, and the sacrifices you have been forced to make. You are exactly the same person you were, and yet you will never be the same again. You’re now one of the 18,000. The half-or-so percent. Whatever anyone has to say about it – however unmentionable the M-word – you just joined an exclusive club. Welcome. You’re in exceptional company…

Links & References

http://content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB02731/clin-audi-supp-prog-mast-brea-reco-2011-rep1.pdf